Repurposing Coal Lands for Economic Development

In its coal heyday, Mingo County, West Virginia was a hub of activity. As many as 30 mines and power plants employed some 3,000 of the county’s 26,000 residents, feeding the economy of the county and the five municipalities within it. Today, only seven remaining power plants and mines remain, offering 700 jobs. The county’s population has shrunk to 23,000.

But as the landscape of industry and employment has shifted, so have the possibilities, and the Mingo County Redevelopment Authority (MCRA) is always looking for new options.

“We see our transition work as continuing a 20-year mission,” says Executive Director Leasha Johnson. “We started when coal mining was booming, but our board recognized that the future would require diversification away from a coal-based economy.”

From Surface Mines to Airports

Part of the challenge in this part of the country is the landscape: the steep mountains and deep gorges hold great beauty, but also great challenges for physical development. However, MCRA recognized the possibility of using old surface mining sites for commercial or industrial development.

“We collaborated with coal companies, land companies and regulatory bodies to identify economic reuses of post mined land, and our efforts lead to the creation of our Land Use Master Plan.” says Johnson. “The Master Plan is a vehicle which has allowed us to jump start economic development activity on former surface mining sites. In some cases, the development was initiated on the front end of the proposed mining activity so that while the coal was being mined, the coal company would configure the land to the rough grade of the post mine land use designation (i.e. airport, highway, golf course, school site, etc.), all in accordance with guidelines of the relevant regulatory body (i.e. WV Department of Environmental Protection, WV Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, etc.), allowing us to leverage significant private sector investment into eventual economic development sites.”

In exchange for their participation, coal companies were granted a permit variance which allowed the post mining land use designation to be changed from “approximate original contour” to one of transportation infrastructure, recreational facilities, and educational facilities.

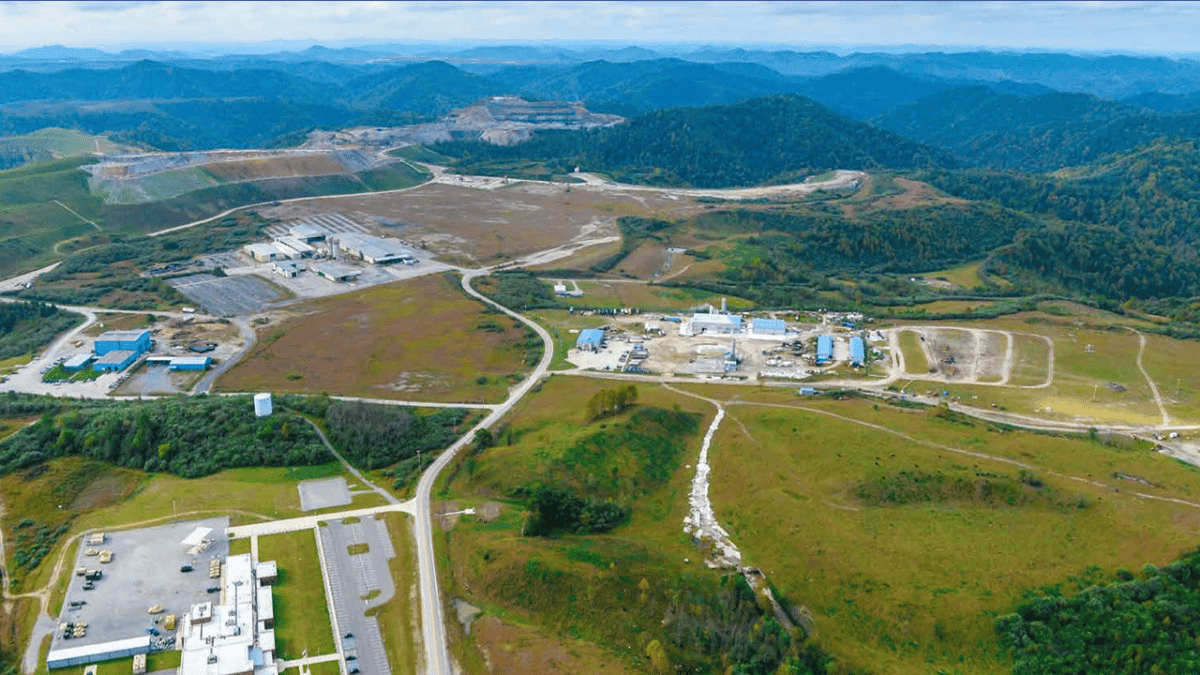

One project that currently sits on a former surface mining site, which is the production of the MCRA’s Land Use Master Plan, is the Mingo County Air Transportation Park, a state-of-the-art general aviation airport with a 5,000’ runway, lighting and wind instrumentation, surrounded by 500 acres which are suited for aviation manufacturing and supply chain businesses. Although development of the area has been slow (much needed federal funding support continues to foster completion of the facility), the project holds promise for economic development and new workforce opportunities.

“We feel that the skill sets of coal miners are easily transferrable to the aviation and aerospace manufacturing industries that we hope to recruit to Mingo County. The welding and electrical engineering skills of displaced coal miners are a perfect fit for these aviation sector jobs,” says Johnson.

Other surface mine developments in Mingo County include a wood products industrial park, construction of 15 miles of the King Coal Highway, development of an 18-hole PGA-style golf course, and exploration into a 150-acre industrial hemp farm.

Building a Unique Recreational Attraction

In addition to former mine sites, Mingo County has another unique asset – large tracts of single-owner, undeveloped land. Decades ago, private land companies acquired thousands of acres in Mingo and surrounding counties with the intent to lease the surface and underground rights to coal companies. Now, as the coal industry dwindles, the land remains.

In 2000, the Hatfield McCoy Regional Recreation Authority negotiated with the private land companies to open 300 miles of cleared trails for All Terrain Vehicles (ATVs), Utility Terrain Vehicles (UTVs) and off-road motorcycles. Today, more than 700 miles of trails run through five counties to create the Hatfield-McCoy Trails System. In exchange for allowing the trails to cross private property, the Recreation Authority provides landowners with a $10 million liability policy.

Some 55,000 riders receive trail permits each year, opening the door for new hospitality businesses to welcome them. Johnson envisions not only hotels and restaurants, but opportunities for construction, tiny cabin manufacturing, and other related businesses.

“We need more places for trail riders to stay, and we need to provide them with additional recreational and leisure opportunities while there here.” says Johnson. “Trails tourism presents a unique opportunity for small business growth in Mingo County, but we’ve learned that displaced coal miners are somewhat risk averse, and that fostering an entrepreneurial spirit in a post coal economy has proven to be difficult. For so many years, we lived in what we call an economic monoculture where nearly every non-public, government or health care worker was employed by the mining industry, either directly, in some form of coal transportation, or in a coal supply chain business. Our workforce has been consumed by the mining industry, and small business development has been stagnant, until now. Now is the time to support the growth of small businesses and grow a more sustainable economy that consists of both manufacturing and small business development.”

According to Johnson, the Hatfield-McCoy Regional Recreation Authority has worked with county development offices to secure and utilize funding from the Appalachian Regional Commission to support trails entrepreneurs with the development of business plans, marketing assistance, and access to capital.

“We’re attracting more and more tourists and growing the industry,” says Johnson. “Now, we’re trying to change the messaging to market Mingo County as more of a tourist destination rather than just a weekend trails getaway.”

Along those lines, the MCRA and others have supported the development of Twisted Gun Golf Course and the Twin Branch Drag Strip, both located on reclaimed surface mines and the product of the Land Use Master Plan.

Infrastructure Challenges

Infrastructure is an ongoing challenge in Mingo County. Although the Air Transportation Park opened in 2012, it wasn’t until recently that it secured funding to provide water and sewer services because it didn’t meet typical federal funding models.

The landscape itself is both a blessing and a curse. Steep and winding roads leading to reclaimed surface mines limit the kinds of industries that can be successful there. Twenty years ago, the Harless Wood Products Industrial Park was developed as an incubator for different types of value added wood manufacturing, but only one manufacturer, a maker of hardwood flooring, located to the park because transporting raw materials and finished products proved to be very difficult on the three mile access road to the reclaimed surface mine site. Since then, the MCRA has attracted other types of businesses to the park that aren’t as hindered by the steep and windy access road.

Broadband is also an issue. Its absence hampers not only the air park, but also the “King Coal Highway” project that runs through Mingo County, as well as most of the county’s other surface mine redevelopment sites.

Building Partnerships

Partnerships have been key to Mingo County’s economic development efforts. MCRA partners with nonprofits and social enterprises like Coalfield Development, government agencies, regulatory bodies, and private sector companies to identify diversification opportunities and to fuel development for the region.

The effective implementation of public/private partnerships has allowed the MCRA and the county to leverage funding through the USDA, as well as the federal POWER initiative via the Economic Development Administration and the Appalachian Regional Commission.

“Our federal partners have been a cornerstone to our transition,” says Johnson. “They’ve provided funding which has fostered much needed infrastructure development, workforce training, and technical support. But their dollars also have fostered more regional collaboration than ever before – and this economic transition is definitely a regional effort.”

Investing in Diversity and Preserving History

Although many residents still long for a single-industry solution, Johnson is focused on diversity.

“We’re not focusing on any one thing,” she says. “We’re all over the board, and we don’t want to leave any stone unturned.”

At the same time, Johnson emphasizes the importance of recognizing the contributions of community members and coal workers that have come before.

“At one point, Mingo County was the heart of the trillion-dollar coalfield. We had an intergenerational pride in the work we were doing,” she says. “There’s a sensitivity when transitioning away from what’s been a community’s life and livelihood. Certainly, there are communities of people that identify the need for transition, but too often they cast so much negativity on lives and families of coal miners who have put their lives at risk for the country. We want to protect that heritage as a part of the transition, to tell the story about where we’ve come from, what coal has done for us, and the opportunities that it has provided to us going forward.”